Insulin Safety: Dosing Units, Syringes, and How to Avoid Hypoglycemia

Nov, 22 2025

Nov, 22 2025

Getting insulin dosing wrong isn’t just a mistake-it can land you in the hospital. One extra unit. One wrong syringe. One miscalculated carb ratio. That’s all it takes to send blood sugar crashing. And it happens more often than you think. In the U.S., nearly 7.4 million people use insulin daily. Many of them are doing it safely. But thousands aren’t-and the reason isn’t always carelessness. Sometimes, it’s because the system itself is confusing.

Why Insulin Units Are Not Like Other Medications

Insulin isn’t measured in milligrams or milliliters like most drugs. It’s measured in units. That’s not just a label-it’s a biological measurement. One unit of insulin isn’t a fixed amount of liquid. It’s the amount that lowers blood sugar by a certain amount in a specific person. This is why using the wrong syringe can be deadly. Most people use U-100 insulin: 100 units per milliliter. That means if you draw up 10 units, you’re getting 0.1 mL. But if you accidentally grab a U-500 syringe-used for severe insulin resistance-you’d get five times the dose. One mistake. One syringe swap. One trip to the ER. Even the labels can trick you. Some pens say "U-100" on the side. Some vials say "100 units/mL." But if you’re used to seeing "IU/mL" or "U/mL," you might assume they’re the same. They are. But not everyone does. And that’s where the real danger hides.The Hidden Math Behind Insulin Dosing

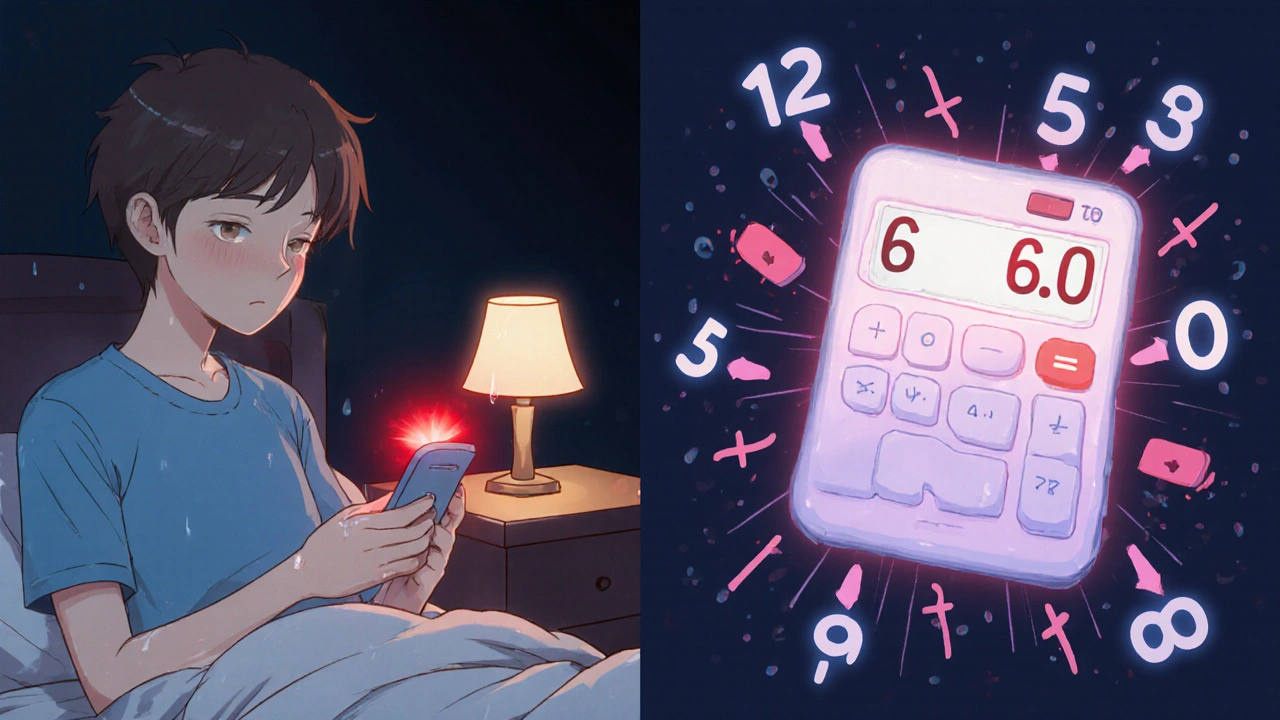

There’s a math problem no one talks about. A study in PubMed found that most online calculators, lab reports, and even journal articles use the wrong conversion factor to turn insulin units into mass (micrograms). The correct factor is 5.18. But 9 out of 10 tools use 6.0. That’s a 15% error. Why does that matter? Because if you’re a researcher, that error skews data. If you’re a doctor, it could lead to wrong dosing recommendations. If you’re a patient, it means your insulin might be less effective than you think-until your blood sugar spikes. Or worse, you compensate by taking more… and then crash. Let’s break down the real-world math you need to know:- Carb ratio: Most people need 1 unit of rapid insulin for every 10-15 grams of carbs. But it can range from 4 to 30 grams per unit, depending on your sensitivity. If you eat 90 grams of carbs and your ratio is 1:12.5, you need 7.2 units. Round up? Down? That’s your call-but be consistent.

- Correction factor: The Rule of 1800 says: 1800 ÷ your total daily insulin = how many mg/dL one unit drops your blood sugar. If your total daily dose is 40 units, then 1800 ÷ 40 = 45. So if your sugar is 220 and you want to hit 120, you need to drop 100 points. 100 ÷ 45 = 2.2 units. You’d give 2 or 2.5, depending on your doctor’s advice.

- Total daily dose: A simple starting point is your weight in kilograms × 0.55. So a 60 kg person might start with 33 units per day. Basal insulin (long-acting) usually makes up 40-50% of that. That’s 13-17 units once daily.

Syringes: The One Tool That Can Kill You

Not all syringes are created equal. U-100 insulin must be drawn with a U-100 syringe. That’s non-negotiable. U-100 syringes are marked in 1-unit increments. They’re usually clear, with thin needles. U-500 syringes? They’re red. They’re thicker. They’re marked differently. If you grab the wrong one, you’re giving yourself a 500% overdose. And don’t assume your insulin pen is safe. Pens are pre-filled and labeled, so they’re safer. But if you’re switching from vials to pens-or from one brand to another-you need to know the difference. Lantus and Basaglar are both insulin glargine. They’re similar. But they’re not identical. When switching from NPH to Lantus, you cut your dose by 20%. Why? Because Lantus is more predictable. Give the same dose, and you risk low blood sugar. Same goes for Tresiba. It lasts longer. If you switch from Lantus to Tresiba, you might need less. But if you switch from Tresiba to Basaglar and try to split the dose for twice-daily use, you can’t just divide by two. You cut it to 80% of the original dose. So 100 units of Tresiba becomes 80 units of Basaglar-split into 40 units every 12 hours.

Hypoglycemia: The Silent Killer

Low blood sugar doesn’t always come with shaking hands or sweating. Sometimes, it just feels like fatigue. Or confusion. Or irritability. You might think you’re just tired. But if your blood sugar drops below 70 mg/dL, your brain isn’t getting enough fuel. If it falls below 50, you could pass out. Below 40, you’re at risk of seizures or coma. The biggest cause? Dosing errors. Taking too much insulin. Not eating after a dose. Exercising without adjusting. Or switching insulins without guidance. Here’s what to do if your sugar is low:- 15 grams of fast-acting carbs: 4 glucose tablets, ½ cup juice, or 1 tablespoon of honey.

- Wait 15 minutes.

- Check again.

- If still low, repeat.

- Once back above 70, eat a snack with protein and carbs-like peanut butter on crackers-if your next meal isn’t for more than an hour.

Titration: When to Add or Cut Units

Adjusting insulin isn’t guesswork. It’s science. For basal insulin (like Lantus or Basaglar), look at your fasting blood sugar over 3-5 days:- If fasting is ≥180 mg/dL → add 8 units

- If 160-179 → add 6 units

- If 140-159 → add 4 units

- If 120-139 → no change

- If 100-119 → consider reducing by 2 units

- If <60 → reduce by 4 or more units

- ≥180 mg/dL → add 3 units to your meal dose

- 140-179 → add 1-2 units

- 100-119 → no change

- 70-99 → reduce by 1 unit

What to Do If You’re Switching Insulins

Switching insulin types is common. But it’s risky if you don’t know the rules.- NPH → Lantus/Basaglar: Reduce total daily dose by 20%

- Lantus → Tresiba: Keep dose the same, but monitor closely for the first week. Tresiba lasts longer, so your sugar might stay stable longer-but it can also hide lows.

- Tresiba → Basaglar (switching to twice-daily): Take 80% of your Tresiba dose, split evenly

- Human insulin → Analog: Start at the same dose. Analogs act faster and cleaner, so you might need less.

steve o'connor

November 23, 2025 AT 02:33I’ve been on insulin for 12 years and the syringe thing still trips me up sometimes. I once grabbed a U-500 by accident because the box looked similar. Scared the hell out of me. Now I color-code everything. Red tape on U-500, blue on U-100. Simple. Lifesaving.

ann smith

November 24, 2025 AT 11:38This post is so important. I wish every new diabetic got this handed to them on day one. So many people don’t realize how tiny the margin for error is. You’re not being paranoid-you’re being smart. Keep sharing this kind of info.

Julie Pulvino

November 24, 2025 AT 18:53My dad switched from NPH to Lantus and didn’t cut his dose. Ended up in the ER with a sugar of 32. He’s fine now, but man-it was scary. The 20% reduction rule saved his life once he figured it out. Please, everyone: when switching insulins, talk to your doc. Don’t guess.

Patrick Marsh

November 25, 2025 AT 02:13U-100 syringes. Not U-500. Always check. Always.

Danny Nicholls

November 27, 2025 AT 00:43That 5.18 vs 6.0 math thing blew my mind 😳 I’ve been using those online calculators for years and never thought twice. Now I’m double-checking everything. Also, glucose gel in the car? YES. I keep one in my glovebox, one in my work bag, and one in my jacket. You never know when your body’s gonna betray you.

Robin Johnson

November 27, 2025 AT 18:46Titration isn’t guesswork. It’s data. Track your fasting sugars for 3-5 days before adjusting. No exceptions. If you’re not tracking, you’re flying blind-and that’s not bravery, it’s negligence. Start a spreadsheet. Use your phone app. Do it.

Latonya Elarms-Radford

November 28, 2025 AT 14:43It’s not just about units or syringes-it’s about the existential weight of living in a body that requires mathematical precision to survive. We are not patients. We are human algorithms. Every dose is a prayer. Every meter reading, a verdict. And yet, the system offers us no grace. Only formulas. Only numbers. Only the cold calculus of survival. Who designed this? Why does our life hinge on a decimal point? And why are we expected to do this alone?

Mark Williams

November 29, 2025 AT 09:27The Rule of 1800 assumes steady-state insulin sensitivity. But in reality, insulin resistance fluctuates due to cortisol spikes, inflammation, even circadian rhythm shifts. That’s why many patients experience inconsistent correction factors. You need to test across multiple time points-fasting, postprandial, nocturnal-to get a true picture. Most clinicians skip this.

Miruna Alexandru

November 30, 2025 AT 11:33Interesting. But you didn’t mention the FDA’s 2022 warning about pen label inconsistencies across manufacturers. Also, the carb ratio range of 4–30 g/unit? That’s not a range-it’s a chaos metric. No standardized protocol. No regulatory oversight. Just guesswork dressed up as science. And you call this safe?

Melvina Zelee

December 2, 2025 AT 04:07Y’all need to chill. I’ve been doing this for 20 years and I just wing it most days. I eat, I check, I dose. Sometimes I’m low, sometimes I’m high. It’s not perfect. But I’m alive. You don’t need to overthink it. Just be kind to yourself. And maybe keep some juice handy. 🙃

Daniel Jean-Baptiste

December 2, 2025 AT 17:10Thanks for the post. I’ve been using Basaglar since last year and switched from Tresiba. Didn’t know about the 80% rule. Just split it 50/50 and thought it was fine. Now I’m adjusting. Small changes matter. Also, I use the same syringe brand every time. Helps me not mix things up.

Shawn Daughhetee

December 4, 2025 AT 06:52One time I forgot to eat after my shot and passed out in the grocery store. No one knew what was wrong. Took 20 minutes for someone to grab juice. Don’t be like me. Tell people. Always.

Justin Daniel

December 5, 2025 AT 06:44Man, I love how this post doesn’t sugarcoat it (pun intended). I used to think I was the only one stressing over a 0.5 unit difference. Turns out we’re all just one syringe swap away from disaster. Thanks for making me feel less alone. Also, Tresiba to Basaglar = 80%? That’s wild. Bookmarking this.

Nikhil Chaurasia

December 5, 2025 AT 16:46When I first started insulin, I thought I was invincible. Then I had a seizure at 3 AM. No one knew. I woke up in the hospital with a IV of D50. That’s when I realized: this isn’t a lifestyle. It’s a full-time job. And the system? It’s rigged. But we’re still here. Still fighting. Still dosing. Still living. Respect.

Holly Schumacher

December 5, 2025 AT 17:34Wow. This is so basic. Everyone should know this. Why is this even a post? Did you really need to write 2,000 words to say ‘don’t use the wrong syringe’? This is like writing an essay on ‘don’t put your hand in fire.’ The fact that this needs explaining is terrifying. And frankly, a little insulting to anyone who’s been paying attention.