Causes of Generic Drug Shortages: Manufacturing and Supply Chain Vulnerabilities

Jan, 21 2026

Jan, 21 2026

Every year, hundreds of essential generic drugs vanish from hospital shelves and pharmacy counters. Not because they’re no longer needed - but because no one can make them reliably. These aren’t rare specialty drugs. They’re the antibiotics, anesthetics, chemotherapy agents, and blood pressure pills that millions rely on daily. And when they disappear, patients suffer. Doctors scramble. Nurses ration doses. The problem isn’t random. It’s built into the system.

Manufacturing Problems Are the Main Culprit

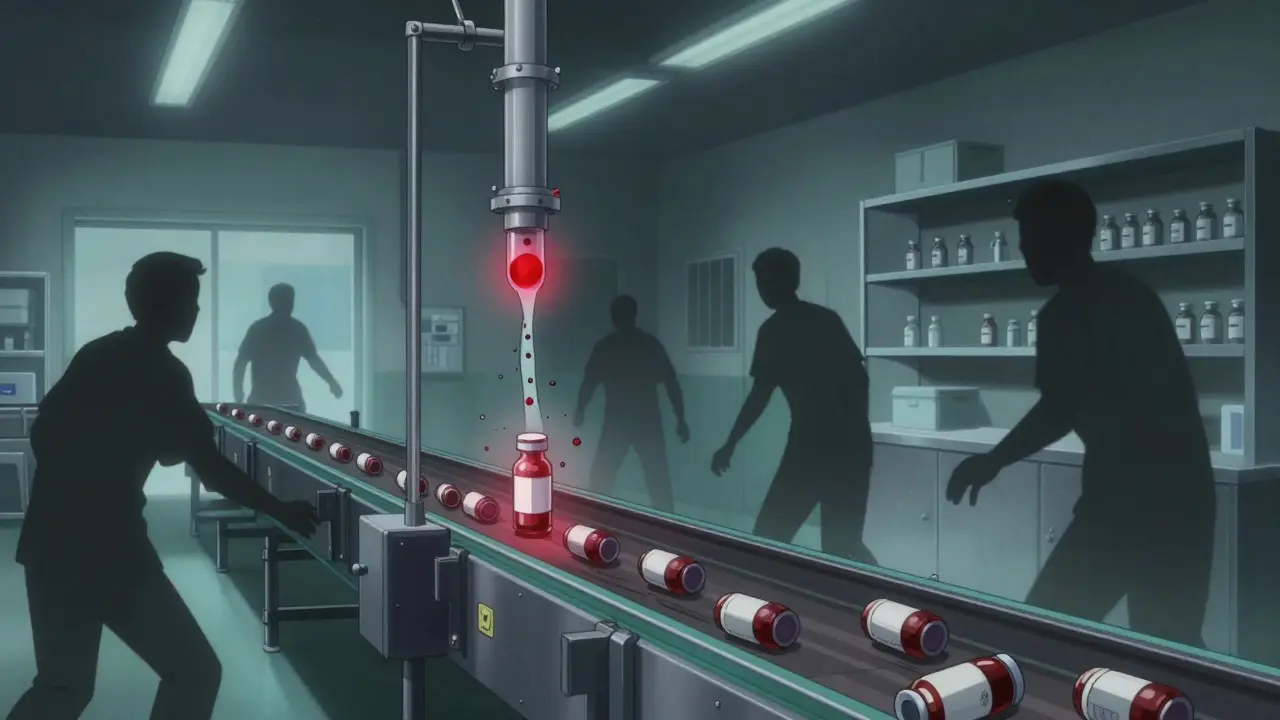

Over 60% of all drug shortages in the U.S. since 2010 trace back to manufacturing failures. Not because factories are old or outdated - but because they’re pushed to run at full capacity with zero room for error. A single contamination event in a sterile injectable production line can shut down a facility for months. One FDA inspection finding a single uncleaned pipe or improper sterilization protocol can halt production of a life-saving drug. These aren’t rare accidents. They happen regularly.

Take the case of a major U.S. hospital in 2022 that ran out of propofol, a common anesthetic. The manufacturer had paused production for six months after an FDA warning about microbial contamination. No backup supplier existed. Patients had to wait for surgery. Some were sent home. This isn’t an outlier. It’s standard. The industry calls it "low to no excess capacity." In other words, manufacturers run their lines 98% full - because there’s no profit in keeping idle machines ready for emergencies.

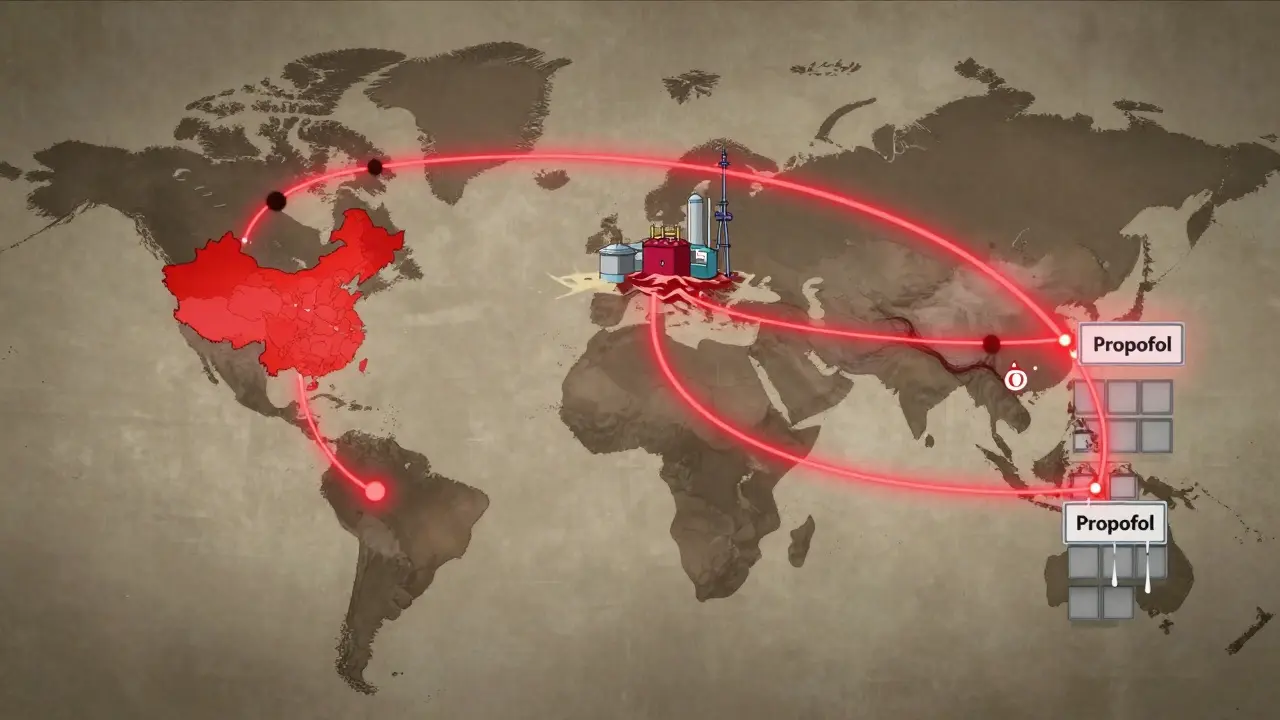

Global Supply Chains Are Fragile

Eighty percent of the active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) used in generic drugs come from just two countries: China and India. That’s not a coincidence. It’s economics. Labor is cheaper. Regulations are looser. But it also means one flood, one political shutdown, or one quality control failure halfway across the world can ripple through American hospitals.

In 2020, a factory in India shut down after an FDA inspection found it was falsifying test results. That one facility produced over 40 different generic drugs - including common antibiotics and heart medications. Within weeks, hospitals across the Midwest reported critical shortages. No one had a backup. No one had stockpiled. The system had been designed to eliminate inventory, not build resilience.

Even when manufacturers try to diversify, they can’t. Building a new API plant in the U.S. costs over $200 million. It takes five years. And once it’s built, the profit margins on generic drugs are often below 15%. Compare that to branded drugs, which can earn 30-40%. Why invest billions into a low-margin product when you can make more money selling a different drug - or just walk away?

One Supplier, One Product

One in five drug shortages involves a medication made by only one company. That’s not competition. That’s a single point of failure. And it’s getting worse. Since 2010, over 3,000 generic drugs have been discontinued. Why? Because no one wants to make them.

Consider a simple generic antibiotic like amoxicillin. It’s been around for decades. The formula is public. The market is saturated. Dozens of companies made it - until they didn’t. Price wars drove margins down. Pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) - the middlemen who control 85% of prescription drug spending - demanded lower prices. Manufacturers responded by cutting costs. They reduced quality checks. They delayed maintenance. They stopped investing in upgrades. Eventually, some just quit.

Now, only two or three companies make amoxicillin in the U.S. If one has a problem - a power outage, a machine breakdown, a regulatory delay - the whole country feels it. There’s no redundancy. No safety net. Just one line of production holding up the entire supply.

Profit Over Preparedness

Generic drugs are supposed to be cheap. And they are - but at a cost. The system rewards the lowest bid, not the most reliable supplier. Hospitals and insurers choose the cheapest version of a drug, even if it’s made by a company with a history of quality issues. Why? Because the PBM gets a cut from the lowest price. The hospital saves money on paper. The patient gets the same pill. But the risk? It’s hidden.

Manufacturers know this. They know that if they raise prices even slightly, they’ll lose the contract. So they cut corners. They delay equipment upgrades. They hire less experienced staff. They skip preventive maintenance. And when something breaks - which it inevitably does - there’s no buffer. No stockpile. No backup plan.

The result? A vicious cycle. Low prices → low profits → poor maintenance → shutdowns → shortages → higher prices (temporarily) → more manufacturers exit → even fewer suppliers → worse shortages. It’s not broken. It’s working exactly as designed.

Who’s Responsible?

It’s easy to blame manufacturers. Or regulators. Or pharmacies. But the truth is, everyone plays a part. Hospitals buy the cheapest drug. PBMs demand lower prices. Regulators inspect but don’t penalize enough to change behavior. Governments don’t fund stockpiles for everyday medicines - only for bioterrorism or pandemics. And patients? They assume the drug will be there. Because it always has been.

Canada has the same generic drug market. But it doesn’t have the same level of shortages. Why? Because they have a national stockpile. Because regulators, hospitals, and manufacturers talk to each other. Because there’s accountability. In the U.S., when a drug goes missing, there’s no central system to track why - or who’s to blame. One in four shortage reports don’t even list a cause.

What’s Being Done?

There are signs of change. In 2023, Congress introduced the RAPID Reserve Act - a bill aimed at creating a strategic reserve for critical generic drugs. It would require manufacturers to report potential shortages earlier. It would offer tax breaks for domestic API production. It’s a start. But it’s not enough.

The American Medical Association is pushing to stop PBMs from excluding drugs that are in adequate supply in favor of those in short supply - a practice that worsens shortages. The FDA is trying to speed up inspections. But none of these fix the core problem: the market doesn’t reward reliability. It rewards the lowest price.

Until we change that, shortages will keep happening. Not because we lack the technology. Not because we lack the knowledge. But because we’ve built a system that profits from fragility.

What This Means for Patients

If you take a generic drug - and most of us do - you’re already living with this risk. You might not notice it now. But if your blood pressure medication suddenly disappears, or your chemotherapy drug is replaced with a less effective alternative, you’ll feel it. Clinicians are already spending 50-75% more time managing shortages than they did a decade ago. That’s time taken from patient care.

There’s no easy fix. But awareness is the first step. Knowing that this isn’t an accident - it’s a design flaw - is power. Demand transparency. Ask your pharmacist: "Is this drug in short supply?" Ask your doctor: "Are there alternatives?" Push for policies that value reliability over price. Because when the next shortage hits, it won’t be someone else’s problem. It’ll be yours.

Ryan Riesterer

January 23, 2026 AT 01:18The systemic lack of buffer capacity in generic drug manufacturing is a textbook case of just-in-time logistics pushed to pathological extremes. When your entire supply chain is optimized for marginal cost reduction rather than resilience, you're not engineering efficiency-you're engineering fragility. The FDA’s inspection regime, while necessary, operates on a reactive rather than predictive model, and the absence of mandated dual-sourcing for critical APIs is a regulatory blind spot with lethal consequences.

Daphne Mallari - Tolentino

January 23, 2026 AT 22:59One cannot help but observe that the current paradigm reflects a profound moral failure in pharmaceutical economics. The commodification of life-sustaining therapeutics-reducing them to line items on a balance sheet-is not merely inefficient; it is ethically indefensible. The notion that profit margins below fifteen percent constitute an untenable business model for essential medicines reveals a disturbing prioritization of shareholder value over public health.

Neil Ellis

January 24, 2026 AT 16:59Imagine if we treated antibiotics like fire extinguishers-every hospital keeps a few extra on the shelf, just in case. We don’t wait for the building to burn down before we buy one. But with drugs? We wait until the ICU is out of dopamine and then act shocked. The system’s not broken-it’s been trained to ignore the warning signs. We need to start rewarding the companies that build redundancy, not punish them for not being the cheapest. Maybe if we gave tax credits for maintaining spare capacity, we’d stop playing Russian roulette with patient care.

Alec Amiri

January 25, 2026 AT 15:27Bro, this is all just corporate greed. No one wants to make cheap drugs because the money’s in the fancy ones. PBMs are the real villains here-they’re the ones squeezing every last penny out of the system. And guess who pays? Us. The patients. The nurses. The old folks who can’t afford to wait for their blood pressure meds. It’s disgusting.

Patrick Roth

January 26, 2026 AT 06:40Actually, you’re all missing the point. Canada doesn’t have shortages because they have a single-payer system that negotiates volume, not because they have a stockpile. The U.S. has the same manufacturers, same APIs, same regulations-it’s the payment structure that’s broken. If you paid manufacturers fairly instead of forcing them into a race to the bottom, they’d invest in quality. Stop blaming the FDA and start blaming Medicare’s reimbursement rates.

Lauren Wall

January 27, 2026 AT 15:40It’s not a shortage. It’s a consequence of choosing cheap over safe. Again.

Kenji Gaerlan

January 29, 2026 AT 12:41why do we even make generic drugs if they keep breakin? just make the brand ones cheaper lmao

Oren Prettyman

January 30, 2026 AT 13:57It is, of course, axiomatic that the structural deficiencies in the generic pharmaceutical supply chain are not attributable to any single actor, but rather emerge as a complex adaptive system phenomenon wherein market incentives, regulatory capture, and cost-containment policies intersect in a manner that systematically disincentivizes redundancy. The absence of mandated minimum inventory thresholds, coupled with the non-enforcement of Good Manufacturing Practice compliance penalties, creates a negative externality wherein the social cost of drug shortages is externalized onto the patient population, while the private actors involved continue to operate under a profit-maximizing paradigm that renders systemic resilience economically irrational. This is not negligence-it is rational behavior within a misaligned incentive structure.