Multicultural Perspectives on Generics: How Culture Shapes Patient Trust and Adherence

Feb, 3 2026

Feb, 3 2026

Why a pill’s color can make someone refuse their medicine

Imagine taking a pill every day for high blood pressure. You’ve been told it’s the same as the brand-name drug-same active ingredient, same dose, same price. But this one is blue. Your grandmother’s medicine was white. You’ve heard stories from your community that blue pills are weak, or even fake. So you stop taking it. This isn’t just about confusion. It’s about culture.

Generic medications make up 70% of all prescriptions sold in Europe and over 90% in the U.S. by volume. They save billions every year. But for many people around the world, the decision to take a generic isn’t just medical-it’s cultural, religious, and deeply personal. And too often, the healthcare system ignores that.

What’s really inside that capsule?

Generics have the same active drug as brand-name versions. But the rest? The fillers, dyes, coatings, and capsules? Those can be completely different. And those differences matter.

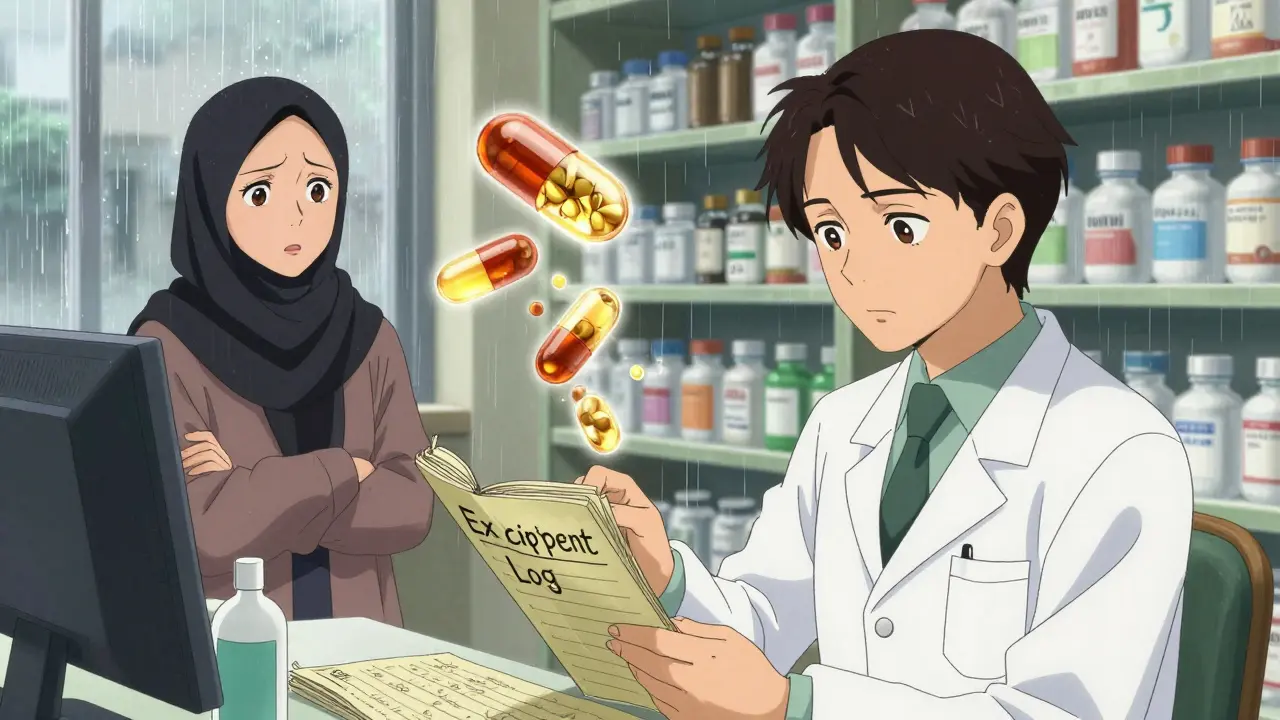

Take gelatin. It’s used in capsules to hold the medicine together. But for many Muslims, gelatin made from pork is forbidden. For Jews, it must be kosher-certified. For some Hindus, animal-derived ingredients conflict with religious beliefs. One pharmacist in Durban told me she once spent two full days calling manufacturers just to find a gelatin-free version of a blood thinner for a Muslim patient. She wasn’t paid extra. She did it because she knew her patient would rather go without than take something that broke their faith.

And it’s not just gelatin. Other common excipients include lactose (problematic for some with dietary restrictions), artificial dyes like Red 40 or Blue 1 (which some cultures associate with illness or death), and even the shape of the pill. In parts of West Africa, round white pills are seen as pure and trustworthy. Oval green ones? Suspicious. In Latin American communities, bright yellow pills are often linked to strong medicine-so a pale generic version can be dismissed as ineffective, even when it’s identical in strength.

Trust isn’t just about science-it’s about history

Why do African American patients report nearly double the concern about generics being less effective than white patients? It’s not because they don’t understand science. It’s because of history.

Centuries of medical exploitation, from the Tuskegee syphilis study to forced sterilizations, have left deep scars. When a patient is handed a pill that looks nothing like the one their doctor used to prescribe, it can feel like another version of the same betrayal: They’re giving you the cheap version because you’re not worth the real thing.

These fears aren’t irrational. They’re rooted in real experiences. A 2022 FDA survey found that 28% of African American patients doubted generics, compared to just 15% of non-Hispanic white patients. In Hispanic communities, language barriers make it worse. If the label doesn’t explain what the pill is in Spanish-or if the pharmacist doesn’t speak their dialect-they’re left guessing. And when you’re already distrustful, guessing can mean not taking the medicine at all.

What pharmacies aren’t telling you

Most community pharmacies don’t have a system to check what’s in a generic pill. Not because they’re careless-but because they’re overwhelmed.

Only 37% of generic drug labels in the U.S. list all inactive ingredients. In the EU, it’s 68%. That means pharmacists in America are often flying blind. A patient asks, “Is this halal?” and the pharmacist has to call three manufacturers, dig through old PDFs, and hope someone replies. One pharmacy chain in Chicago started keeping a printed binder with excipient info for all generics they stock. It took six months to compile. Now, it saves 80% of the time.

Training is even scarcer. Only 22% of U.S. community pharmacies have formal training on cultural considerations for generics. That means most pharmacists learn on the job-by accident, by trial, by listening. And that’s not enough.

What works: Real solutions from real places

Some places are getting it right.

In Toronto, a pharmacy network partnered with local imams and rabbis to create a list of halal and kosher-certified generics. They printed it in multiple languages and hung it behind the counter. Patients started asking for it by name. Adherence for diabetes meds jumped 34% in six months.

In South Africa, a clinic in Soweto began training community health workers to explain generics using culturally familiar metaphors. Instead of saying “same active ingredient,” they said, “It’s like the same maize meal, but from a different mill. Same nutrition, different bag.” Patients understood. No one had to explain excipients.

Even big companies are starting to move. Teva, the world’s largest generic maker, launched its Cultural Formulation Initiative in 2023. By the end of 2024, they’ll have documented all excipients in their top 15 drug categories. Sandoz is doing the same. It’s not charity-it’s smart business. The U.S. alone has $12.4 billion in unmet generic medication needs among minority populations. Fixing this isn’t just ethical. It’s profitable.

What you can do-whether you’re a patient or a provider

If you’re a patient:

- Ask your pharmacist: “What’s in this pill besides the medicine?” Don’t be shy. You have a right to know.

- If you’re uncomfortable with a generic, ask for a different brand or formulation. Many alternatives exist.

- Bring your old pill bottle to the pharmacy. Sometimes, matching the color or shape helps with trust.

If you’re a healthcare provider:

- Don’t assume everyone understands what “generic” means. Use simple analogies.

- Keep a printed or digital list of excipients for your most common generics. Update it quarterly.

- Partner with community leaders. They know what questions their people are afraid to ask.

- Train your staff. Even two hours a month on cultural competence makes a difference.

If you’re a policymaker or drug manufacturer:

- Require full excipient disclosure on all generic labels-globally.

- Invest in multilingual, culturally adapted patient education materials.

- Work with religious and cultural organizations to certify medications.

The future isn’t just cheaper medicine-it’s better medicine

Generics aren’t the problem. The problem is treating culture as an afterthought.

By 2027, 65% of top generic manufacturers plan to build cultural considerations into their product design. That’s progress. But it shouldn’t take a market report to make us care.

Medicine isn’t just chemistry. It’s connection. It’s trust. It’s respect.

When a Muslim woman takes her blood pressure pill because she knows it’s halal, when a Black father believes his child’s generic asthma inhaler works because it looks like the one his doctor uses, when a Filipino elder swallows their diabetes tablet without fear because the color feels right-that’s when generics truly work.

That’s the goal. Not just to fill prescriptions. But to heal communities.

Why do some people refuse generic medications because of their color or shape?

In many cultures, the appearance of a pill-its color, shape, or size-is linked to beliefs about strength, purity, or safety. For example, in parts of West Africa, white round pills are seen as trustworthy, while green or oval pills may be viewed as weak or fake. In Latin America, bright yellow pills are often associated with powerful medicine. When a generic looks different from the branded version a patient used before, they may assume it’s less effective-even if the active ingredient is identical. These beliefs aren’t based on science, but on cultural experience and community stories, which are just as real to the patient.

Are there generic medications that don’t contain gelatin?

Yes. Many generic medications use vegetarian capsules made from hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (HPMC), which is plant-based and acceptable for Muslim, Jewish, Hindu, and vegan patients. However, manufacturers aren’t always required to list this on the label. Pharmacists must check with the manufacturer or use specialized databases to confirm. Some pharmacy chains now keep lists of gelatin-free generics, especially for common medications like antibiotics, blood pressure drugs, and diabetes treatments.

How can I find out what’s in my generic medication?

Ask your pharmacist directly. Request the full list of inactive ingredients (excipients). If they don’t have it, ask them to contact the manufacturer. You can also check the FDA’s DailyMed database or the European Medicines Agency’s website for official labeling. In the U.S., only about 37% of generic labels include full excipient details, so you may need to dig deeper. Don’t rely on the package insert alone-ask for the manufacturer’s technical sheet.

Why don’t all pharmacies have cultural competence training?

Most pharmacies are understaffed, underfunded, and focused on speed. Cultural competence training isn’t required by law in most countries, and it’s not reimbursed by insurance. Only 22% of U.S. community pharmacies have formal training programs. Many pharmacists learn through experience or personal interest. But without institutional support, this knowledge stays scattered. The solution? Mandating training as part of pharmacy licensing and funding it through public health grants.

Is there a global standard for halal or kosher medications?

No official global standard exists yet. Some countries, like Malaysia and Saudi Arabia, have national halal certification bodies for pharmaceuticals. In the U.S. and Europe, certification is voluntary and done by private organizations like the Islamic Food and Nutrition Council of America (IFANCA) or the Orthodox Union (OU). This creates confusion. A pill certified halal in the U.S. may not be recognized in Indonesia. Until there’s international alignment, patients and pharmacists must rely on local trusted sources and detailed ingredient lists.

How do cultural beliefs affect adherence to chronic disease meds?

For chronic conditions like hypertension or diabetes, adherence is already low-around 50% globally. In culturally diverse groups, it drops even further when patients distrust generics due to appearance, ingredients, or past medical trauma. One study showed that African American patients who believed generics were inferior were 3 times more likely to skip doses. When pharmacists took time to explain ingredients and validate concerns, adherence improved by up to 40%. Cultural understanding doesn’t replace medical advice-it makes it stick.