QT Prolongation with Fluoroquinolones and Macrolides: Monitoring Strategies

Dec, 1 2025

Dec, 1 2025

QT Prolongation Risk Calculator

This tool helps assess risk of QT prolongation from antibiotics. Based on clinical guidelines, it calculates risk factors and provides actionable recommendations for patients taking fluoroquinolones or macrolides.

Patient Risk Factors

When you take an antibiotic like azithromycin or ciprofloxacin, you’re usually thinking about killing the infection-not about your heart. But for some people, these common drugs can quietly disrupt the heart’s electrical rhythm, leading to a dangerous condition called QT prolongation. This isn’t rare. It’s not theoretical. It’s happening in hospitals, nursing homes, and outpatient clinics every day. And if you’re not watching for it, it can turn into Torsades de Pointes-a life-threatening arrhythmia that can strike without warning.

What QT Prolongation Really Means

The QT interval on an ECG measures how long it takes the heart’s ventricles to recharge between beats. When this interval gets longer than it should, the heart’s electrical system becomes unstable. That’s QT prolongation. It doesn’t always cause symptoms. But when it does, it can trigger Torsades de Pointes, a chaotic, fast heart rhythm that can lead to sudden cardiac arrest. Fluoroquinolones and macrolides are two major classes of antibiotics linked to this risk. Fluoroquinolones include drugs like ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, and moxifloxacin. Macrolides include erythromycin, clarithromycin, and azithromycin. These aren’t obscure drugs-they’re among the most prescribed antibiotics in the world. But not all of them carry the same risk.Which Antibiotics Are the Biggest Risks?

Not all fluoroquinolones are equal. Moxifloxacin has the highest risk among them. Ciprofloxacin is lower risk. Levofloxacin? Even lower. But here’s the catch: even low-risk drugs can become dangerous when combined with other factors. For macrolides, the risk ladder is clear: erythromycin > clarithromycin > azithromycin. Erythromycin is the worst offender-it blocks the same potassium channel in the heart as antiarrhythmic drugs like sotalol. Azithromycin, while still carrying a warning, is much safer in comparison. But if you’re giving azithromycin to a 78-year-old woman with kidney disease, low potassium, and taking a diuretic? Suddenly, that “low-risk” drug becomes a ticking time bomb. The FDA and major guidelines now warn against using fluoroquinolones for simple infections like uncomplicated UTIs-especially in older women. Why? Because the risk of a fatal arrhythmia often outweighs the benefit. Yet, these drugs are still overused. A 2025 study found that many older women in long-term care facilities were getting fluoroquinolones for minor urinary infections while already on other QT-prolonging drugs. That’s not just poor prescribing-it’s preventable harm.How QT Prolongation Happens: The Science Behind the Risk

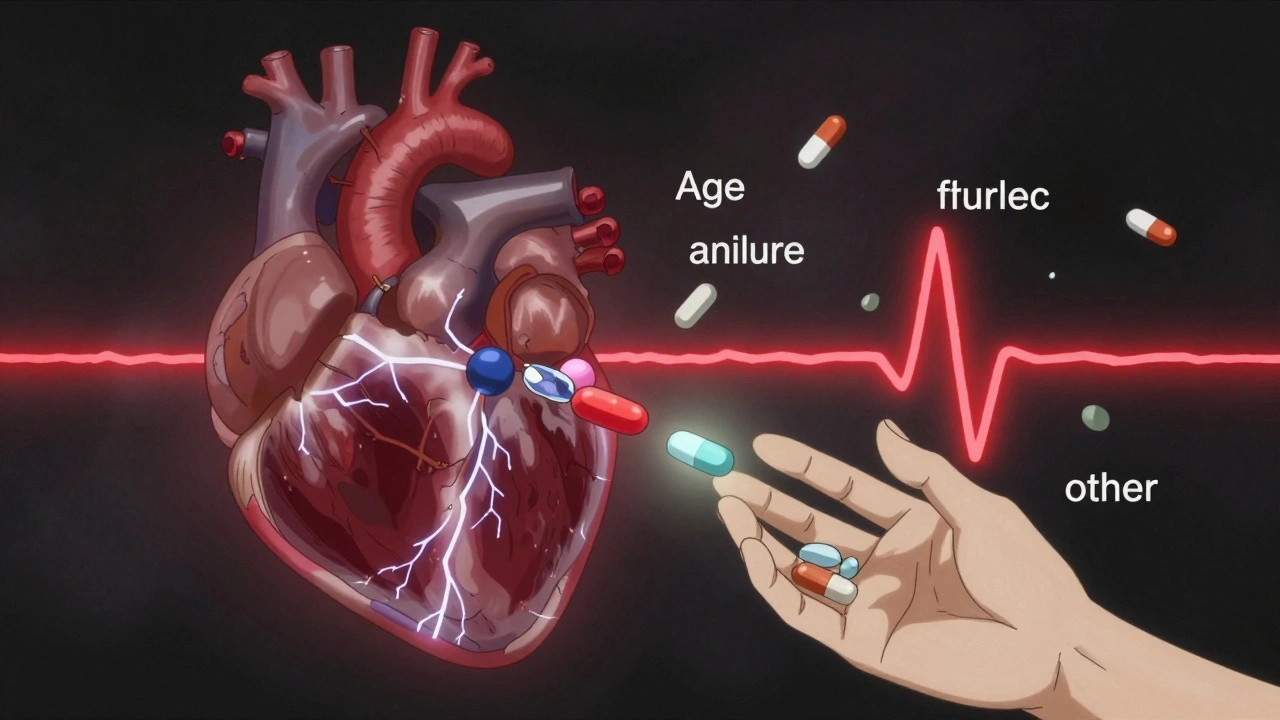

These antibiotics don’t just kill bacteria-they interfere with the hERG potassium channel in heart cells. This channel helps the heart reset after each beat. When it’s blocked, repolarization slows down. The result? A longer QT interval. The effect is dose-dependent and can be worse with IV administration. It’s also time-dependent: the biggest changes often happen within the first 24 hours after the first dose. This isn’t just about the drug. It’s about the person taking it. Risk factors pile up like traffic cones on a highway. Age over 65. Female gender. Low potassium. Low magnesium. Heart failure. Kidney disease. Taking other QT-prolonging drugs like antifungals, antidepressants, or antiarrhythmics. Even something as simple as vomiting or diarrhea that causes electrolyte loss can tip the balance. Critically ill patients are especially vulnerable. In the ICU, you might find someone on IV ciprofloxacin, IV erythromycin, with low magnesium, on a diuretic, with sepsis-induced arrhythmias, and a pacemaker. That’s not a patient. That’s a perfect storm.

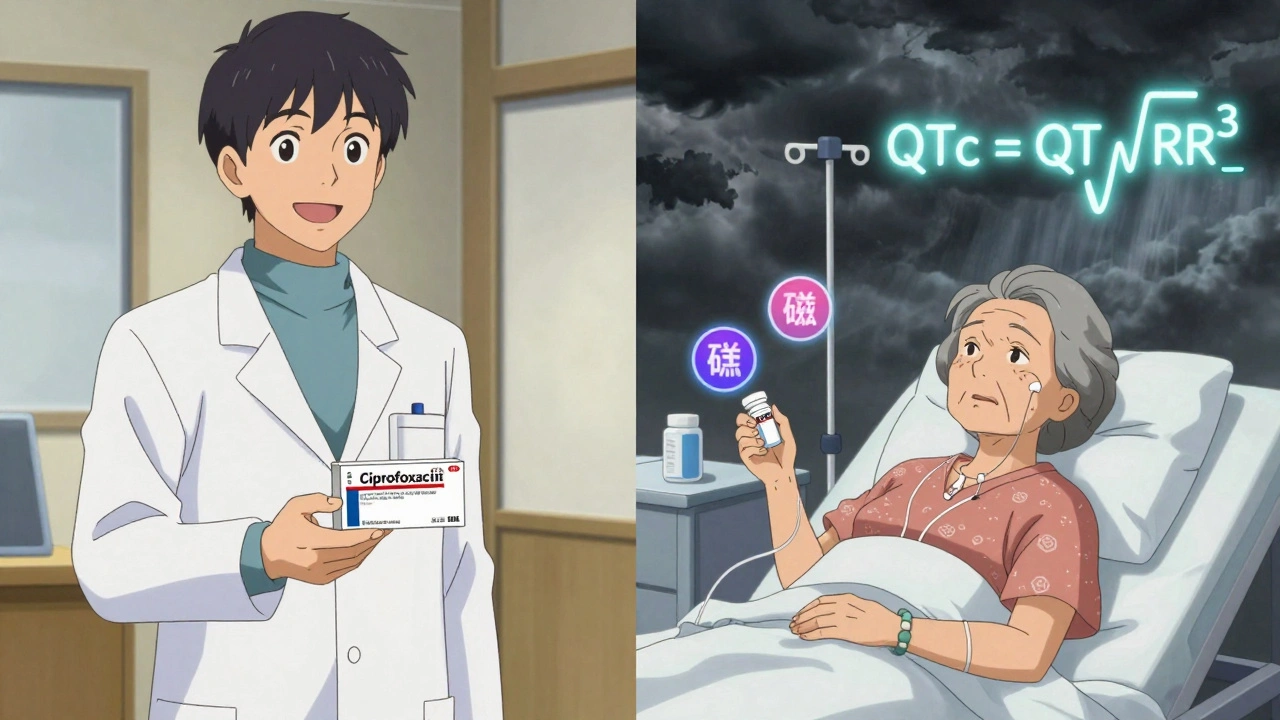

How to Measure QT Correctly-And Why Most Clinicians Get It Wrong

You can’t just look at an ECG and guess. QT measurement needs precision. And correction for heart rate is critical. For decades, doctors used Bazett’s formula (QTc = QT / √RR). But it’s flawed. At high heart rates, it overcorrects. At low heart rates, it undercorrects. That means you could miss a dangerous prolongation-or falsely flag a normal one. The Fridericia formula (QTc = QT / √RR³) is now the gold standard. It’s more accurate, especially in older patients and those with heart disease. Studies show it predicts 30-day and 1-year mortality better than Bazett’s. If your hospital still uses Bazett’s, you’re working with outdated tools. And don’t forget: some conditions make QT look longer than it is. Bundle branch blocks. Pacemakers. Wide QRS complexes over 140 ms. These aren’t QT prolongation-they’re measurement artifacts. Misinterpreting them leads to unnecessary drug stops or dangerous delays.When to Monitor: The Real-World Monitoring Strategy

You don’t need to check every patient. But you can’t ignore high-risk ones. The British Thoracic Society 2023 guidelines give clear direction:- Before starting any macrolide, get a baseline ECG. If QTc is over 450 ms in men or 470 ms in women, don’t start.

- Repeat the ECG one month after starting therapy.

- For fluoroquinolones, check ECG 7 to 15 days after starting, then monthly for the first three months.

What to Do When QT Prolongation Shows Up

If the QTc goes over 500 ms-or increases by more than 60 ms from baseline-stop the antibiotic. Immediately. No exceptions. Don’t wait for symptoms. Don’t hope it’ll resolve on its own. Then fix what you can. Check potassium and magnesium. If potassium is below 4.0 mmol/L, replace it. If magnesium is under 2.0 mg/dL, give IV magnesium sulfate. That’s not just supportive care-it’s lifesaving. Studies show correcting these electrolytes cuts arrhythmia risk by more than half. Also review every other drug the patient is on. Is there a statin? An antipsychotic? A proton pump inhibitor? Many of these also prolong QT. You might need to switch or stop them too.Why This Matters Beyond the ECG

This isn’t just about avoiding one bad outcome. It’s about changing how we think about antibiotics. Fluoroquinolones and macrolides are powerful tools. But they’re not harmless. The overuse of fluoroquinolones for simple UTIs, bronchitis, or sinus infections has been called “an epidemic of inappropriate prescribing.” Antimicrobial stewardship programs now explicitly recommend avoiding fluoroquinolones for uncomplicated infections in older adults, especially women. Alternative antibiotics like nitrofurantoin or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole carry no QT risk and are just as effective for many cases. The bottom line? Every time you write a prescription for ciprofloxacin or azithromycin, ask: Is this really necessary? And if yes-what’s the patient’s real risk? A simple ECG before starting, a quick check of electrolytes, and a review of other meds can prevent a cardiac arrest. And that’s not just good medicine. It’s basic safety.What’s Next: The Future of QT Risk Management

Researchers are building tools that combine patient data-age, gender, kidney function, electrolytes, other meds-into a single risk score. Imagine a point-of-care app that tells you, “This patient has a 12% risk of QT prolongation with this combo.” That’s coming. And it will change prescribing. Genetic testing for long QT syndrome is also becoming more accessible. Some people have inherited mutations that make them hypersensitive to drug-induced QT prolongation. They might never know it-until they take azithromycin and go into Torsades. For now, the tools we have are simple: know the drugs, know the risks, check the ECG, fix the electrolytes, and question every unnecessary prescription.Can azithromycin really cause dangerous heart rhythms?

Yes, though the risk is low compared to other macrolides like erythromycin. Azithromycin can prolong the QT interval, especially in patients with existing risk factors like older age, low potassium, kidney disease, or taking other QT-prolonging drugs. While serious events like Torsades de Pointes are rare, they’ve been documented. The risk is higher with IV use and in high-risk populations like elderly women in long-term care.

Is QT prolongation always reversible?

Most often, yes-if caught early. Stopping the offending drug and correcting electrolytes (potassium and magnesium) usually reverses the prolongation within days. But if Torsades de Pointes develops and isn’t treated immediately, it can lead to sudden death. That’s why early detection and intervention are critical.

Do I need an ECG for every patient on ciprofloxacin?

No, but you should for those with risk factors. If the patient is young, healthy, with no heart disease, normal electrolytes, and not on other QT-prolonging drugs, routine ECGs aren’t needed. But if they’re over 65, have kidney issues, low potassium, or are on diuretics or antidepressants, get a baseline ECG before starting and repeat it 7-15 days later.

Why is the Fridericia formula better than Bazett’s for QT correction?

Bazett’s formula overcorrects at high heart rates and undercorrects at low heart rates, leading to inaccurate QTc values. Fridericia’s formula (QTc = QT / √RR³) adjusts more accurately across a wider range of heart rates. Studies show it better predicts mortality and reduces false positives and negatives. Many guidelines now recommend Fridericia as the standard for clinical use.

Can I use a different antibiotic instead to avoid QT risk?

Absolutely. For uncomplicated UTIs, nitrofurantoin or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole are preferred over fluoroquinolones. For respiratory infections, amoxicillin or doxycycline are often safer alternatives to macrolides. The key is matching the antibiotic to the infection-and choosing the one with the lowest cardiac risk, especially in vulnerable patients.

Declan O Reilly

December 2, 2025 AT 02:58Man, I’ve seen this play out in the ER too many times. Someone comes in with a UTI, gets cipro because it’s ‘broad-spectrum,’ and 36 hours later they’re coding. No ECG. No electrolytes. Just ‘it’s just an antibiotic.’ We’re treating infections like they’re traffic tickets-quick fine, move on. But hearts don’t care about convenience.

It’s not the drug. It’s the mindset. We’ve normalized risk because the consequences are rare. But rare doesn’t mean impossible. And when it hits, it hits hard.

Someone’s grandma dies quietly in a nursing home because no one checked QTc. No lawsuit. No headline. Just another statistic. That’s the real tragedy.

Conor Forde

December 2, 2025 AT 04:19Oh here we go-another ‘antibiotic = cardiac time bomb’ lecture. Let me guess, next you’ll tell me aspirin causes internal bleeding and water causes drowning?

Yes, QT prolongation exists. But let’s not turn every 70-year-old with a UTI into a cardiac ICU candidate. The risk is microscopic for most. The real problem? Doctors who over-test and under-think. You want to monitor? Fine. But don’t scare people into avoiding life-saving antibiotics because some guy on Reddit says ‘check the Fridericia formula.’

Also, ‘moxifloxacin is worst’? Tell that to the guy with sepsis who needs it. Risk-benefit, people. Not fear-benefit.

patrick sui

December 3, 2025 AT 08:50Just wanted to say-this is exactly why we need point-of-care AI risk calculators. Imagine if your EHR auto-pops up: ‘Patient: 74F, CKD Stage 3, on furosemide, starting azithromycin → QTc risk: 18%. Recommend: check K+, Mg++, consider nitrofurantoin.’

That’s not sci-fi. That’s 2025. We’re still using paper ECGs and Bazett’s in 2025? 🤦♂️

Also-huge props to the author for calling out the ‘low-risk’ myth. Azithromycin isn’t safe-it’s just *less dangerous*. And in polypharmacy elderly? It’s still a grenade with the pin pulled.

Let’s stop treating antibiotics like candy. 🧪❤️

Priyam Tomar

December 4, 2025 AT 23:33Everyone here is overcomplicating this. The answer is simple: don’t prescribe fluoroquinolones or macrolides unless absolutely necessary. Period.

If you’re giving azithromycin for bronchitis, you’re not a doctor-you’re a liability. The CDC says it’s useless for viral infections. So why are you writing it?

And don’t give me the ‘but my patient is allergic to penicillin’ excuse. There are 12 other antibiotics. You’re just lazy. Or worse-you’re getting kickbacks from Big Pharma.

Stop pretending you’re saving lives. You’re just buying time until the arrhythmia hits.

Jack Arscott

December 6, 2025 AT 11:09Big respect to the OP for laying this out so clearly. ❤️🩺

Just had a patient last week-82yo, on amiodarone, got cipro for a ‘bladder infection.’ QTc went from 440 to 512 in 48 hours. No symptoms. No warning. Just a silent countdown.

Fridericia saved her. Bazett’s would’ve missed it.

Also-yes, potassium and magnesium are the unsung heroes here. Give IV MgSO4 and you’ve done more than most hospitals in a year.

Stop guessing. Start measuring. 🙏

Michelle Smyth

December 7, 2025 AT 17:46How quaint. A 3000-word treatise on QT intervals, as if this were a medical journal and not a Reddit thread.

Let’s be honest-this is just another example of clinical overreach disguised as ‘best practice.’ We used to treat fevers with ice baths. Now we ECG every elderly woman who sneezes.

And Fridericia? How many of you even know how to calculate it manually? You’re outsourcing critical thinking to algorithms. That’s not medicine. That’s spreadsheet worship.

Next you’ll be mandating genetic testing before prescribing ibuprofen.

Patrick Smyth

December 9, 2025 AT 11:06My mother died from this.

She was 76. Had a UTI. Got azithromycin. No ECG. No labs. Just ‘it’s fine, it’s just a pill.’

Three days later, she collapsed in the kitchen. No CPR. No warning. Just… gone.

The hospital said ‘it was natural causes.’

It wasn’t. It was negligence wrapped in a prescription pad.

I’ve been screaming about this for two years. No one listens.

Now I’m just waiting for the next one.

Linda Migdal

December 9, 2025 AT 12:01So now we’re telling American doctors they can’t use the best antibiotics because some European guidelines say so?

We’ve got the best healthcare system in the world. We don’t need your ‘risk stratification’ or your ‘Fridericia formula.’

If you’re scared of QT prolongation, don’t prescribe it. But don’t make the rest of us jump through hoops because you’re afraid of a lawsuit.

Fluoroquinolones save lives. Don’t let fear cripple medicine.

Tommy Walton

December 11, 2025 AT 05:52QT prolongation = silent killer.

ECG before azithromycin? Mandatory.

Check K+? Mandatory.

Stop cipro for UTIs? Mandatory.

Why? Because we’re not playing roulette with hearts.

And yes, I’m that guy who checks the QTc before I prescribe.

Y’all can keep your Bazett’s. I’ll take Fridericia. 🚀

James Steele

December 12, 2025 AT 04:28Let’s not pretend this is a novel insight. The hERG channel blockade has been documented since the 90s. The real scandal? The fact that these drugs remain first-line for uncomplicated infections while safer alternatives exist.

It’s not ignorance. It’s inertia.

Pharma reps push fluoroquinolones because they’re profitable. Hospitals use them because they’re convenient. Patients take them because they’re told ‘it’s just a pill.’

We’ve turned pharmacology into a commodity. And the heart? It’s just collateral damage in the efficiency equation.

Wake up. This isn’t science. It’s systemic moral decay dressed in white coats.

Louise Girvan

December 12, 2025 AT 06:25They’re watching you. The FDA. The CDC. The pharmaceutical conglomerates. They want you to think this is about ‘patient safety’-but it’s really about control.

Why do they care about QT intervals? Because if you start checking ECGs before every antibiotic, you slow down prescribing. Slower prescribing = less profit.

And don’t tell me ‘it’s for the elderly.’ They’ve been pushing this for 20 years. Why now? Because they’re scared. Scared that people will realize antibiotics aren’t magic.

They’re not protecting you. They’re protecting the system.

Check your ECG if you want. But don’t believe the narrative.

They’re lying. And you’re the experiment.