Thalidomide and Teratogenic Medications: History and Lessons in Pregnancy Safety

Dec, 31 2025

Dec, 31 2025

Thalidomide wasn’t meant to hurt anyone. In the late 1950s, it was sold as a gentle sedative and a cure for morning sickness - a drug doctors trusted, and pregnant women relied on. By 1961, more than 10,000 babies worldwide were born with missing or stunted limbs, deafness, blindness, or internal organ damage. The cause? A pill their mothers took before they even knew they were pregnant. This isn’t a horror story from a distant past. It’s a warning written in human flesh - and one that still shapes how we think about medicine today.

The Rise of a ‘Perfect’ Drug

Thalidomide was developed in West Germany in 1954 by Chemie Grünenthal. It was marketed as safe, non-addictive, and effective for nausea, insomnia, and anxiety. Unlike other sedatives of the time, it didn’t cause respiratory depression. Doctors loved it. Pharmacies stocked it. Pregnant women took it by the millions. In some countries, it was even sold over the counter. By 1958, it was available in 46 nations. No one questioned its safety in pregnancy - because no one had tested it properly.

The real danger was hidden in timing. The drug only caused damage during a narrow window: between 34 and 49 days after the last menstrual period. That’s roughly weeks 5 to 7 of pregnancy. Many women didn’t know they were pregnant then. By the time they missed a period, the damage was already done. Even one dose could trigger severe malformations. The most common? Phocomelia - limbs that looked like flippers, with hands or feet attached directly to the torso. Other defects included missing ears, cleft palates, heart problems, and blindness.

The Moment the World Realized Something Was Wrong

In 1960, doctors in Germany and Australia started noticing something odd. Babies were being born with rare, devastating birth defects - and they kept showing up in the same places where thalidomide was heavily prescribed. In Germany, pediatrician Widukind Lenz began collecting cases. In Australia, obstetrician William McBride noticed a spike in phocomelia cases at Sydney’s Women’s Hospital. Neither knew the other was investigating.

McBride wrote a letter to The Lancet in June 1961, directly linking thalidomide to birth defects. Lenz called Grünenthal on November 15, 1961, demanding they pull the drug. Within days, Germany pulled it. The UK followed on December 2. But in the United States, the tragedy never unfolded - because one woman refused to sign off on it.

Frances Oldham Kelsey, a medical officer at the FDA, kept rejecting the application from Richardson-Merrell, the U.S. distributor. She asked for more data on fetal safety. The company pressured her. She held firm. Her skepticism saved untold thousands of American babies. She became a national hero - and the reason U.S. drug laws changed forever.

The Aftermath: How Medicine Changed Forever

Before thalidomide, drug approval was a formality. Companies submitted minimal data. Testing on pregnant animals? Rare. Long-term studies? Almost never. After 1961, everything changed.

In 1962, the U.S. passed the Kefauver-Harris Amendments. For the first time, drug makers had to prove both safety and effectiveness before selling a product. They had to disclose side effects. They had to conduct clinical trials - including on pregnant animals. Similar laws followed in Europe, Canada, and beyond.

The UK created the Committee on the Safety of Medicines in 1963. Australia and Germany established national drug monitoring systems. Suddenly, teratogenicity - the ability of a drug to cause birth defects - became a mandatory part of every new drug review. Today, if a medication could affect a fetus, it carries a black box warning. Pregnancy tests are required before prescriptions. Contraception is mandatory for women taking high-risk drugs.

Thalidomide’s Second Life: From Tragedy to Treatment

Here’s the twist: thalidomide didn’t disappear. It came back - and it’s saving lives now.

In 1964, a doctor in Peru named Jacob Sheskin gave thalidomide to a leprosy patient suffering from painful skin sores. The sores vanished. That was erythema nodosum leprosum (ENL). By 1998, the FDA approved thalidomide for ENL. Then, in 2006, it got a second approval - for multiple myeloma, a deadly blood cancer.

Why? Scientists discovered thalidomide blocks the growth of new blood vessels. Tumors need those vessels to grow. Cut them off, and the cancer starves. In clinical trials, thalidomide improved progression-free survival from 23% to 42% in myeloma patients. Overall survival jumped from 75% to 86%.

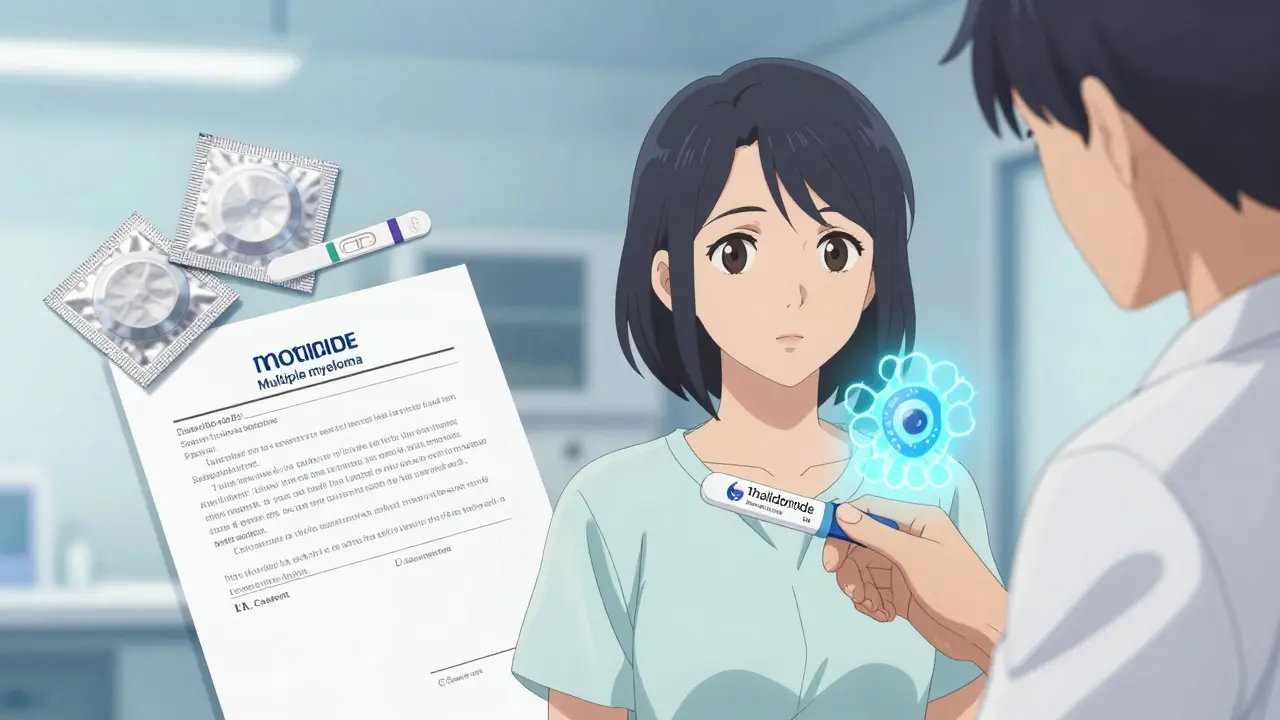

But the side effects are brutal. Up to 60% of patients develop nerve damage - numbness, tingling, pain in hands and feet. That’s why it’s never given casually. Today, every prescription is tracked through the System for Thalidomide Education and Prescribing Safety (STEPS). Women must use two forms of birth control. They must take monthly pregnancy tests. Men must use condoms - because thalidomide can be in semen.

By 2020, global sales reached $300 million - almost all from cancer use. It’s a drug that killed, and now heals. But only under ironclad rules.

The Science Behind the Horror

For decades, no one knew how thalidomide caused birth defects. In 2018 - 60 years after the first affected baby was born - scientists finally found the answer.

They discovered thalidomide binds to a protein called cereblon. This protein normally helps regulate genes that guide limb development. When thalidomide attaches to it, cereblon breaks down key transcription factors. Without them, arms and legs don’t form properly. The same mechanism also explains why it kills cancer cells - it disrupts proteins cancer cells need to survive.

This isn’t just academic. Knowing the exact mechanism helps scientists design safer drugs that target cancer without touching cereblon in embryos. It’s the kind of knowledge that turns tragedy into progress.

What We Still Don’t Know - And Why It Matters

Even today, we don’t fully understand why some babies are affected while others aren’t. Is it genetics? Dosage? Timing? We still can’t predict who’s at risk. That’s why the rule remains simple: if a drug is known to be teratogenic, don’t take it during pregnancy - even if you think you’re not pregnant.

And it’s not just thalidomide. Other drugs - like isotretinoin (Accutane), valproic acid, and certain chemotherapy agents - carry the same risks. The lesson isn’t just about one drug. It’s about trusting science over convenience. It’s about asking: What if this harms a baby who hasn’t even been born yet?

Legacy of a Tragedy

The Science Museum in London has a permanent exhibit on thalidomide. Medical schools teach it in every country. It’s not just history - it’s a living lesson. Every time a doctor checks a patient’s pregnancy status before prescribing a drug, every time a pharmacist asks, ‘Are you pregnant or planning to be?’, they’re honoring the thousands of children who didn’t survive.

Thalidomide taught us that drugs aren’t just chemicals. They’re forces that can shape life - or end it - in ways we can’t always see. The greatest danger isn’t the drug itself. It’s the belief that we already know enough.

Stewart Smith

January 1, 2026 AT 03:05Man, I still get chills reading this. One pill. One tiny mistake. And entire lives changed forever. We think we’re so smart now, but this is a reminder that hubris kills.

Emma Hooper

January 2, 2026 AT 23:38Thalidomide didn’t just kill babies-it killed complacency. And now we’ve got a whole industry built on fear, which is kinda ironic. But hey, at least no one’s giving out prenatal meds like candy anymore. 🙌

Marilyn Ferrera

January 3, 2026 AT 14:55Frances Kelsey deserves a statue. Not just in the FDA lobby-in every medical school. Her refusal to bend saved lives because she asked the right question: ‘What if we’re wrong?’

Branden Temew

January 5, 2026 AT 06:16It’s wild how the same molecular mechanism that maims embryos also starves tumors. Evolution doesn’t care about our moral boundaries-it just binds proteins. Thalidomide is a brutal teacher: science isn’t neutral. It’s a mirror. And sometimes, it shows us our own arrogance.

Deepika D

January 5, 2026 AT 10:35Let’s not forget-this isn’t just about drugs. It’s about how we treat the most vulnerable. The unborn. The voiceless. The ones who can’t say ‘no.’ Every time a doctor asks, ‘Are you pregnant?’-they’re holding a little piece of justice. And we owe that to the kids who never got to hold their own hands.

Also, shoutout to the global moms who had to fight for recognition after the fact. Their pain didn’t vanish when the drug was pulled. It just got quieter. And we still don’t listen well enough.

Today’s cancer patients taking thalidomide? They’re living proof that redemption is possible. But only if we never stop watching. Never stop asking. Never stop caring.

Darren Pearson

January 5, 2026 AT 23:44The Kefauver-Harris Amendments represent a paradigm shift in pharmacovigilance, establishing a regulatory epistemology predicated on empirical rigor rather than commercial expediency. The institutionalization of teratogenic risk assessment, particularly through the integration of embryotoxicity screening in preclinical trials, remains one of the most consequential advancements in twentieth-century biomedical governance.

It is worth noting that the absence of robust pharmacokinetic data regarding placental transfer in early studies constituted a fundamental methodological failure-a lacuna now rectified by OECD guidelines 414 and 422.

Joy Nickles

January 7, 2026 AT 08:39ok but like… why did they even THINK it was safe for pregnant women?? Like?? Did anyone even open a textbook?? I mean, come on. Also, I read somewhere that the company knew and covered it up?? And now they’re like ‘oops’?? I’m so mad. 😡😡😡

Martin Viau

January 7, 2026 AT 09:54Canada did it right. We didn’t approve it. We didn’t need to. American pharma’s greed almost cost us too. We’re lucky our regulators had backbone. And no, I’m not buying your ‘but it’s just one drug’ excuse. It’s the system that’s broken.

Robb Rice

January 8, 2026 AT 17:16Interesting how the same protein-cereblon-is both the villain and the hero. The drug doesn’t change. We just learned how to control it. That’s the real lesson: knowledge is the only real safety net.

Chandreson Chandreas

January 9, 2026 AT 17:52Life finds a way… even through poison. 🌱💔 Thalidomide is like a dark mirror: it shows us how fragile life is, and how powerful our choices are. We hurt. We learn. We heal. And we try again. 🙏

Retha Dungga

January 11, 2026 AT 01:34we are all just stardust trying not to kill babies with pills 🌌😭

Bennett Ryynanen

January 12, 2026 AT 06:04My cousin was born with phocomelia in ‘62. She’s 62 now. Still kicks ass. Still hates when people say ‘you’re so brave.’ Nah. I’m just here. And so is she. Thalidomide didn’t win. We didn’t let it.

Kayla Kliphardt

January 13, 2026 AT 18:10It’s not just about pregnancy tests and warnings. It’s about trust. Who do we trust with our bodies? And why? That’s the question this story forces us to ask.

Jenny Salmingo

January 14, 2026 AT 21:07My grandma took thalidomide in ‘59. She didn’t know. She thought it was just for sleep. She still cries when she sees babies with limb differences. She says she wishes she could’ve held them. This isn’t history. It’s family.

Harriet Hollingsworth

January 16, 2026 AT 01:16And yet, here we are in 2025, still giving out opioids to pregnant women without proper warnings. Some lessons? We just never learn.